India’s largest export to the world may be the idea of curry. A colonial construct, the Indian curry is present in varied forms in countries as diverse as the UK and Japan, in the Caribbean islands, in Mauritius, Thailand and Sri Lanka with age old links with Indian populations, not to mention in the US, Scandinavia and virtually every other country influenced by English food, where tikka masala rules the roost.

Except that no one in India knows what tikka masala is –we do have butter chicken and chicken tikka, two allied dishes, which are restaurant dishes, not home dishes. And no one across the country cooks “curry” or calls it such in their language.

Even that most famous pan-Indian “curry”, present from Bengal to Andhra, the “egg curry”, a food for the masses that originated most likely in the late 19th century, is called a dimer dalna or ande ka kutt by Bengali or Telugu speakers. (Poultry farming was promoted by the English for Europeans in India; hen eggs and chicken were not acceptable to a majority of upper caste Hindus as the birds were regarded as scavengers, according to KT Achaya in The Illustrated Foods of India, and even in Ain-i-Akbari, where a list of permitted bird meat is listed, such as goose and duck, chicken is missing, so upper-class Muslims too preferred duck eggs and the like.)

In Indian homes, we have various terms to describe what westerners generally call “curry”. A gravied dish may have shorva or rasa or be a pulusu, khurma, dalna, a dry vegetable may be simple sukka or sookhi. In Indologist Sandford Arnot’s collection of Mughlai recipes from the 1830s, a sharp distinction is made between the “composition of the kormah” and “the ordinary receipt for making curry in England, which is so simple that any one may reduce it to practice”, as he writes.

Sanford Arnot lists Omelette recipe (Photo: @avtansa)

Confronted with the sharp and pungent tastes of the Subcontinent and unable to comprehend the complexity of spicing in Indian cooking, the Victorians invented a rather timid commodity called the “curry powder”. Curry—after the Tamil word kari, meaning pepper or more correctly something sharp, as in the karipatta. (Kari has a synonymous use in Hindi or other Sanskrit based languages, descriptors that we still use today to connote something that is opposite of sweet–khari boli, khari baat, khara paani, even khari biscuits of Bombay-Pune.)

Initially, there were three different curry powders named after the presidencies—Bengal, Madras, Bombay, all seemingly random spice combinations with a reduced amount of black pepper that gave pungency to medieval Indian dishes, but some red chillies, that had been introduced to India by the Portuguese, and other spices such as coriander seeds, fennel, saffron but no turmeric and so on. (I have a collection of recipes by a 19th century English Colonel’s wife, should anyone be further interested.)

The Victorians –in England—took to curry that could be rustled up using mass-produced curry powder; dishes that were milder than Subcontinental food but more flavourful that European repast. Rich homes (as indeed Queen Victoria’s) started having curry regularly at the dining table, and the fashion spread every where colonial interests and trade went.

Todays book I Recommend is this by Food Historian Karen Foy. How Kitchens During Victorian Time with the introduction of Curries by Queen Victoria. pic.twitter.com/1DrtNyUuxp

— Dr Kim Macthomas (@KimMacthomas) May 6, 2022

In Japan, if you are uncomfortable eating a wide variety of sashimi, teppanyaki, or soba and udon noodles, a safer bet is the kare (curry) that can come within bread, with rice or with noodles. The Japanese curry is something no one in India would recognise as stemming from the Subcontinent—but it did. Curry was introduced in fact to Japan in the Meiji era of the late 19th century when Anglo-Indian officers of the British Royal Navy brought the curry powder, a British invention, to the island country. By the mid-19th century, curry over rice and cutlets (there is a reason katsu curry is the most popular dish with millennial Indians) had become part of the “western” foods (yoshoku) incorporated into Japanese food.

When curry did not arrive via England, but went to other countries via migrating Indian populations, it remained distinctly different from the sweet-mild neither full bodied and complex nor really pungent spice mixes that Indians use for different dishes in different regions and seasons.

In Mauritius, where the mid-19th century was seeing another colonial enterprise—the large-scale transfer of human populations from poor parts of British India—Cari as it is called in Mauritian Creole is a beloved national dish even today. And that is because it carries with it the memories of the Indian forefathers who landed in this distant land from Bengal and Andhra, Maharashtra and Bihar (everywhere other than prosperous Punjab it would seem) to work as indentured labour in the sugarcane fields and factories, producing the precious spice, sugar, for European consumption with cheap labour.

This Indian diaspora initially survived on just daal, rice and chatnee —piment ecrase, a mix of African chillies, lime, and a dash of sugar, is still served in Mauritius as the most popular condiment, with almost everything, from the dal pakora like chilli bites and dholl puri (dal puri), the national dish, to sandwiches, baijas (bhajiyas) and meals.

As time passed, and the Indian-origin dwellers started concocting hybrid flavours with a mix of African European and Indian influences with local ingredients, various forms of cari or spiced, Indian-ish dishes emerged. I was in Mauritius recently deep diving into the local food tradition and how it connects back to India (very closely indeed), and I was struck by the fact that spice mixes for different styles of cooking, say fried fish, or gravied vegetables or biryani, are all different.

In Mauritius, various “garam masala” mixes are available in the market, as also in homes. These use Madagascar spices, which are dry roasted and then powdered and blended in various proportions. This is an idea of spicing that is pretty similar to how different Indian communities cook—not with a generic “curry powder” of European imagination.

What makes Mauritian cari different from Indian is ironically a lack of pungency. Since pepper is a spice that has historically been exported to the world from Kerala, and is not an African spice, it is not really found in the “garam masala”, which is more fragrant than hot.

Heat is imparted from the small bird’s eye chillies of Africa (similar to what you’d find in Goa), these go into the chatnee or chilli, as it is simply called, as also the achards (from achar) that use similar-yet-different spices from Indian achari masalas. Mustard seeds, turmeric, green chillies but vinegar (instead of amchoor, dried mango, another Indian ingredient)—to pickle fruit and vegetables such as apples and cabbage.

The idea of a thick masala in which vegetables and meats can be braised is uniquely Indian—even ancient Indian, it can be conjectured. It can be traced back to Vedic practice of sanctifying food by cooking it in ghee to render it pure or “pucca khana”. Ginger and turmeric were thus fried in ghee as common flavouring agents, even before the use of so many spices became prevalent in regional culinary cultures. (An aromat like cardamom and sharp flavour via pepper were added to finish the dish, even as late as the 17th-18th centuries). This idea of a green aromatic paste fried in oil seems to have travelled via trade to a culture such as Thai, where in fact the Thai curry is not the Anglicised “curry” at all.

Gaeng—meaning a wet, savoury dish enriched with thick paste—is how the Thai curry is correctly named, instead of the generic “red” or “green” curries of westernised parlance. Coconut milk replaced ghee and yoghurt (as in southern India, where milk-based products are less common than in the Indo-Gangetic pain).

Gaeng ped pak (red #veggie #curry) in #Bangkok near Bangrak market. Gosh, I love the #vegan food here in Thailand!!!! pic.twitter.com/baoX7RqZdJ

— Madame eats well (@madameeatswell) April 29, 2015

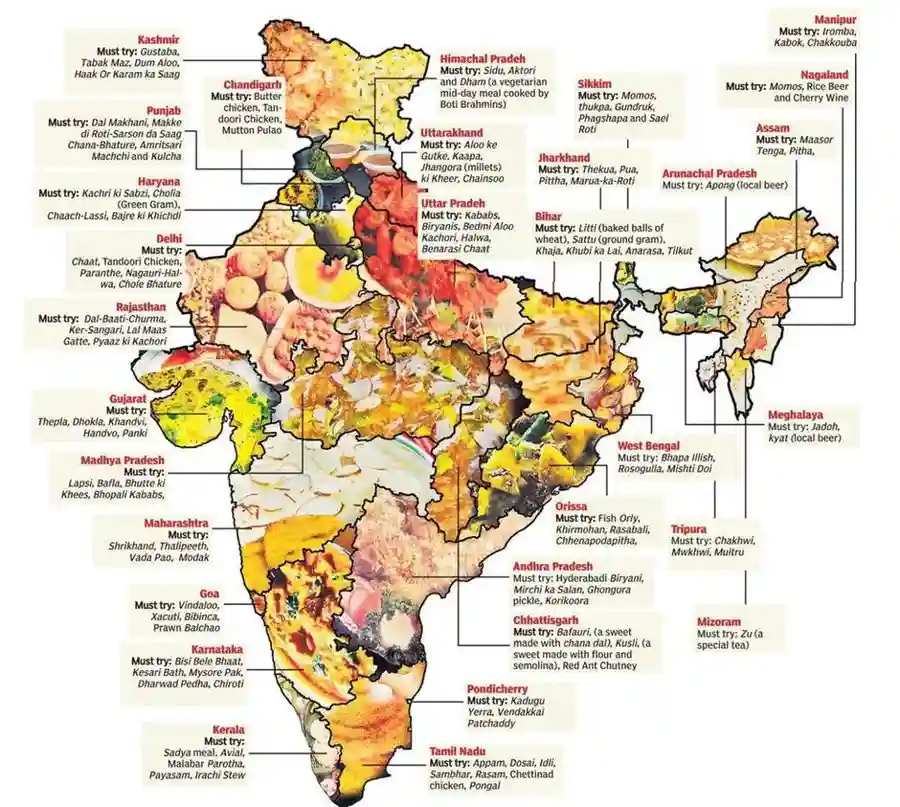

The “curry” then is a reductionist way of approaching Indian and Indian-influenced culinary cultures. It’s time we stopped referring to our food as that, and also encourage others to think of the diversity and complexity of our regional cuisines—beyond curry.

(Anoothi Vishal is the author of Mrs LC's Table. She is also a columnist and food writer, specialising in cuisine history, culinary links between communities and regions. Views expressed are personal and exclusive to India Narrative)