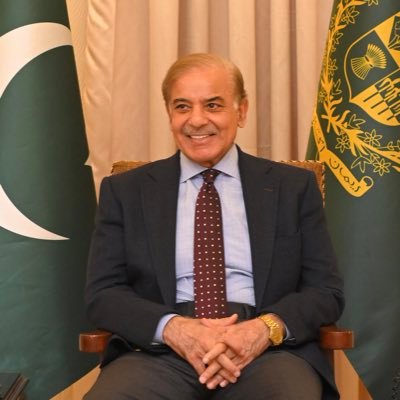

The 16 months of outgoing Shehbaz Sharif government in Pakistan saw shrinking of democratic rights of citizens and opening constitutional windows for the military to exercise more control in deciding several key aspects of the functioning of the state.

Total 27 bills were passed by the National Assembly in the last 18 days of the last session of the House. Majority of them were okayed so hastily that they were not even read on the floor of the House and clueless parliamentarians just voted for them. Disappointed senior PML-N leader and former Pakistan PM, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, thus said that it “was the worst Assembly of the Pakistan history.”

Pakistan’s outgoing government recently made some hasty amendments to existing laws. I look at what they are and how it will impact the country’s politics as well as politicians. For BBC Urdu: https://t.co/ORZrthzYTT pic.twitter.com/e3Des015kW

— Sahar Baloch (@Saherb1) August 9, 2023

Most notable among these bills are the Official Secrets (Amendment) Bill, 2023, Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (Pemra) bill, the Protection of Journalists and Media Professionals (Amendment) Bill, 2023 and the National Commission for Minorities Act, 2023.

Considered a draconian legislation, the Official Secrets Bill was passed in its original form on August 1 and when the media and political parties including those in the ruling coalition protested, certain clauses were modified.

The bill seeks to broaden the military’s grip on tracking even social networks if deemed to be against “norms”. All sorts of modern communication and digital platforms are said to have been included in the ambit of the law – for example, vloggers and bloggers, hitherto untouched, will have to face the music if they deviate as per laid down norms.

The bill also defines “documents” as to explain that it will include “any written, unwritten, electronic, digital, or any other tangible or intangible instrument” related to the military’s procurements and capabilities.

Likewise, the definition of “enemy” introduced in the proposed law states: “Any person who is directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally working for or engaged with a foreign power, foreign agent, non-state actor, organisation, entity, association or group guilty of a particular act… prejudicial to the safety and interest of Pakistan.”

Experts term this section “against the principles of natural justice” as it treats unintentional contact at par with planned espionage.

The law empowers the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Intelligence Bureau (IB) to raid and arrest a citizen over the suspected breach of official secrets, while simply disclosing the name of a secret agent will also be considered an offence. Though amendments made on August 8 made it necessary that sleuths will have to procure an arrest warrant before nabbing a person for the suspected crime.

Taking cue from May 9 attacks on military installations by supporters of now jailed former PM Imran Khan, the Act has termed it an offence if “someone accesses, intrudes, approaches or attacks any military installation, office, camp office or part of building”.

At present, the offence is restricted to such movement during the time of war only, however, the new legislation has expanded this to peacetime as well.

The law empowers the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) and the officials of intelligence agencies to investigate suspects for violation of the Official Secrets Act.

Information Minister Marriyum Aurangzeb, under pressure from media fraternity and coalition partners to subdue legislation on media regulations, ultimately got the crucial Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (Pemra) bill through on the last day at the eleventh hour.

The bill, as feedback on Aurangzeb’s social media accounts make it clear, was considered as “black law” by most of mainstream and social media personalities in Pakistan as it grants too much power to Pemra chief that many independent anchor persons and columnists feel threatened. The bill also was not clear whether the Parliament, through its committee, will appoint the Pemra chief or will it be arbitrarily picked up.

Aurangzeb however managed to get it passed with a clause that protects the monetary settlement of an employee post -retirement and sacking from the job within two months.

The legislation for establishing the commission for religious minorities curiously seems to be good in intent, but it was not debated in the House properly giving it a haze of secrecy that how a national commission will come into being and how provinces will constitute it in case assemblies and Parliament stay in suspension for long. Its provisions say that it will comprise six Hindus, four Christians, two Sikhs, one Parsi, one Kalash, one Bahai, one Buddhist and two Muslim members.

Similar ambiguities or fear of military’s increasing control prevail about all other legislations which went through the National Assembly sans any sufficient, or no, discussion at all.

Like Abbasi, many members of the ruling coalition were similarly disheartened by the way Pakistan Parliament functioned in the last 16 months, and in the last leg its last session particularly.

In his speech on the last day, PPP lawmaker Syed Khursheed Shah said that he would endorse whatever Abbasi stated on the floor of the House, but he also reminded the Parliament that “worst democracy is better than best dictatorship”.

Also Read: Why a military-backed caretaker government could seal Imran Khan’s fate in Pakistan