Last week, viewers of Shark Tank India would have seen a rather unusual pitch win—by a Delhi restaurant chain, Daryaganj, whose founder’s grandfather was ostensibly the chef who invented butter chicken. This then is a column devoted to the legacy Delhi dish, butter chicken, and how it kick started the restaurant revolution in post Partition India.

Butter Chicken is a restaurant invention—the first dish possibly in India to have been invented by one particular restaurant, which became so popular and got copied by so many that it is to be found all over today, in all sorts of “Mughlai” or “Indian” restaurants, in India and internationally. So much so, that it is rare to find a generic pan “Indian” restaurant menu without a mention of this dish in some form or the other.

In the UK, Delhi’s butter chicken inspired the chicken tikka masala, once dubbed as Britain’s “national dish”. But it would be good to remember that while butter chicken is an Indian invention, chicken tikka masala is not an Indian dish, it is a British invention!

The Partition of India saw a huge displacement of populations, but while it was a tragic event, one of the fallouts was the emergence of a new culinary culture in India. As refugees started arriving in Delhi from what was then west Punjab—from towns such as Peshawar and Gujranwala, they brought with them their own memories of food, tastes, and cooking methods.

Even before the actual Partition in 1947, the early 1940s had begun to see a trickle of migration into Delhi and towns of northern India such as Dehradun and Shimla from western Punjab. Some of these Punjabi immigrants established small restaurants in New Delhi to cater to the British and American soldiers posted in the city due to World War II.

Iconic restaurants such as Kwality (established in 1940) are a throwback to those days when American GI soldiers would patronise the new Connaught Place establishments for ice cream and then, later, simple Anglo-Indian snacks such as mutton chops and cutlets. Kwality was opened by PL Lamba along with his brother in law Iqbal Ghai (who also founded the Gaylord chain).

Delhi’s iconic Kwality restaurant reopens with nostalgia-drenched makeover – THE WEEK https://t.co/AvUva4bKNN pic.twitter.com/MgXlxeiKaX

— Delhi Informer (@delhiinformer) December 8, 2018

Post Partition, as this clientele changed, and Punjabi refugees from Pakistan started pouring in, the food served at these restaurants changed too. The refugees who came in to Delhi were more enterprising than the old Delhi residents, where the elite did not eat out much and had cultural preferences towards food cooked at home fresh everyday. There were a few kebabchis and naanbhais, and chaat and mithai vendors were patronised.

Chaat was sold by the khomchawallas, or wandering cooks selling these piquant delights from their cane baskets outside home and havelis. There were also “wedding cooks” or those specialist bawarchis (cooks) called in for weddings or big occasions that necessitated a community feast. But in general, eating out was rather something frowned upon and restaurant retail was thus sluggish, as I have written in my book Business On A Platter, that traces the history of restaurants in India as well as what makes this a very tricky business.

This culture of eating in primarily (at least for the elite and the moneyed) changed with the arrival of the new immigrants from the Punjab. As the older Muslim elite left for Pakistan, their food culture diminished, and newer tastes started coming into their own—often driven by necessity.

My friends Sumit and Chiquita Gulati from the Gulati’s (Pandara Road) family remember how Sumit’s grandfather arrived in Delhi with virtually nothing and set up a redi or pushcart selling chole kulche at India Gate. Chole or Pindi (named after Rawalpindi) Chana was a Punjabi dish, unknown in Delhi, UP and other parts of northern India. It arrived along with kulche and bhature in Delhi, post Partition, as a cultural legacy of the refugee families.

The iconic Gulati’s at Pandara Road, New Delhi. Famous for its butter chicken and dal. #Travel #Food #Delhi pic.twitter.com/BY0tON2FtV

— Raghav (@raghavmodi) February 2, 2020

PL Lamba, the founder of Kwality, found a cook to make bhature in Dehradun—the cook too was a migrant from western Punjab. And as the old clientele of Anglo-Indians, British and American GI soldiers changed in the aftermath of partition, restaurants such as Kwality too started serving Punjabi snacks, including chole and the football-sized bhature Kwality has been famous for since then, made by this cook. The fermented fried bread had been unknown in Delhi before the 1940s.

Old Delhi communities had patronised dishes such as bedmi, fried bread without any leavening, stuffed with a flavourful pithi of ground and spiced dal and served with halwa and a gravy of potatoes.

Bedmi-aloo-halwa was the quintessential Delhi breakfast, a cousin of the countless poori-aloo or kachori-aloo traditions all over the Hindi heartland, where these dishes were served for breakfast, and each of the gravies and pooris varied in flavour according to the region you traversed—from Kanpur to Benares to Kolkata, with its radha ballabi (kachori that is stuffed with green peas in season) and a gravy of potato that can be made either watery, UP style, or aloo dum, the Kolkata invention inspired by the dum cooking of Lucknow. In New Delhi, however, the post partition brunch became chole bhature, as populations and tastes changed, though, you may still find bedmi aloo in what we now call “old Delhi”.

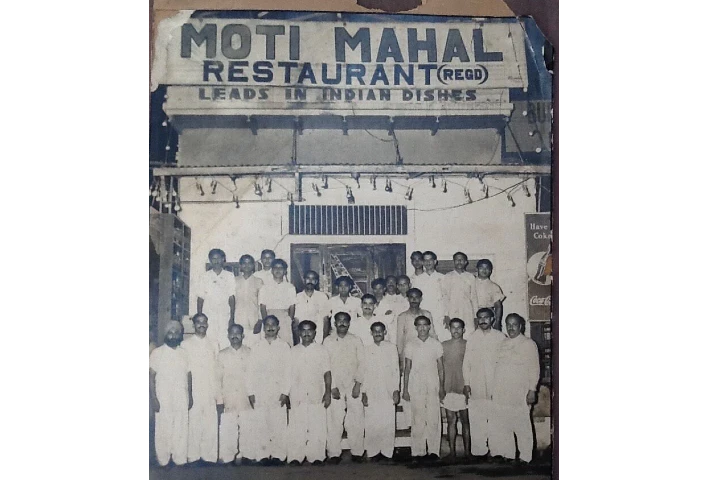

A sleepy, slow, and mostly unorganised restaurant retail by way of street vendors and halwai shops was also soon to change. It all started with Moti Mahal in Daryaganj. The small eatery had come up in 1947, set up also by immigrants from western Punjab. This new eatery started selling tandoori food. Amit Bagga and Raghav Jaggi, founders of Daryaganj restaurant, say Jaggi’s grandfather was the original chef there, and constructing a tandoor in itself was a task.

In Delhi when another fellow refugee made him a Tandoor oven, he, along with two other friends, purchased a small space in Daryaganj and set up the legendary Moti Mahal restaurant, introducing the delicious tandoori food to the residents of Old Delhi (11/) pic.twitter.com/lihpdfNh1w

— The Paperclip (@Paperclip_In) May 10, 2022

Delhi that had been used to its naans, khameeri rotis or the fried pooris and kachori (bedmi) did not know the Punjabi clay oven used to bake breads in the villages. The tandoor, a contraption modelled after the Central Asian tannur, was initially used to bake rotis in. But restaurants in Peshawar had eventually started grilling things like marinated chicken tikkas in it. The enterprising immigrants now thought of selling this style of tandoori rotis and tikkas in Delhi, post 1947.

Jaggi’s grandfather, Kundal Lal Jaggi managed to find another immigrant skilled in assembling tandoor s to make an oven for the fledgling eatery. And from here, they started selling the first tandoori bites in Delhi. This was “fast food”, easier, quicker, fresher and more hygienic (for restaurant retail) than the older style food, and with the wave of migration, it found new patrons. Tandoori became so popular that soon other restaurants started selling it too.

Well it's a post partition story and it all started with 3 friends:

Kundal Lal Jaggi, Kundal Lal Gujral and Thakur Das who worked in Lahore where they worked together in a Dhaba pic.twitter.com/JqqGHVrlSG— vaibhav 🐼🐻 (@momos27i) December 11, 2021

But the older Delhi clientele wanted gravied dishes too, so Jaggi, according to his family, one day put left over (and drying) chicken tikka in a gravy full of tomatoes and makhan (butter). And thus was born chicken makhni, in a makhni gravy—the “mother sauce” for butter chicken.

Tomatoes used in the makhni gravy were also an ingredient not too popular in Delhi and also the rest of India. But they had found more popularity in the frontier provinces and Punjab after the British had introduced large-scale farming of this vegetable in India. Not indigenous to India, the tomato was a south American plant that had been brought to Europe by the Spanish, had endured centuries of mistrust when it was considered poisonous and thus used only for ornamentation, before being accepted for culinary use. In India, as the British promoted its farming, it was regarded as food for the foreigners and its use was highly restricted within Indian homes where dishes used a variety of souring agents from kachri powder and amchoor to imli and kokum in the south.

But the tomato was cheap. And it was also full of glutamates that give “umami” to food—a sensation of meatiness or deliciousness. So we can conjecture, as it gained some acceptance in Punjab, restaurants in Peshawar and Lahore may have started using it as a souring agent.

The Makhni invention was a brainwave that proved to be highly successful because here was now a dish full of delicious umami, easy and not expensive to make as compared to the laborious Mughal-style gravies, which were initially food for the aristocrats and rich and thus took pride in using expensive and often elusive ingredients and spices.

Before it was invented within a restaurant, most of India’s food such as poori-kachori, or the Mughlai gravies were essentially food of homes (and well-to-do homes) adapted for restaurant retail. And an older clientele, culturally used to eating high quality, freshly cooked similar food at home, naturally looked down upon this “outside” food. Chaat and mithai which were not made at home but always by commercial cooks were successful because this was food not accessible ordinarily.

With tandoori and makhni gravy coming into being, a newer style of food was added to this very small repertoire of restaurant dishes that did not have any parallel within homes. To add to this, the new dishes could be quickly and cheaply assembled. They were the perfect restaurant foods and their subsequent popularity bears testimony to the fact.

As butter chicken began to be copied by all manner of restaurants, the original recipe, simple and where the taste of tomatoes and just butter stands out, began to be tweaked too—garam masala, loads of cream, sugar, cooks with different competencies added all these often to mask imprecise cooking, and patrons depending on what taste they were exposed to developed their own favourites. In the late 1990s and 2000s, upscale or luxury restaurants took

up this dish to turn out butter chicken risottos and so on, turning a common man’s dish on its head.

And now the wheel has come a full circle with Daryaganj, with the original recipe, growing outlets furiously. It is remarkable however that a dish that had sparked India’s first restaurant revolution in the 1950s has never really gone out of vogue.

Also Read: From Amritsar to Georgia—the humble Kulcha’s extraordinary journey to Caucasia

(Anoothi Vishal is the author of Mrs LC’s Table. She is also a columnist and food writer, specialising in cuisine history)