Events in a tale or a story are easier to remember and recall as they form part of a seamless narrative but in real life this doesn’t happen. There is no smooth flow from one happening to another as several other things take place in between the two. Then how does one recollect events and incidents?

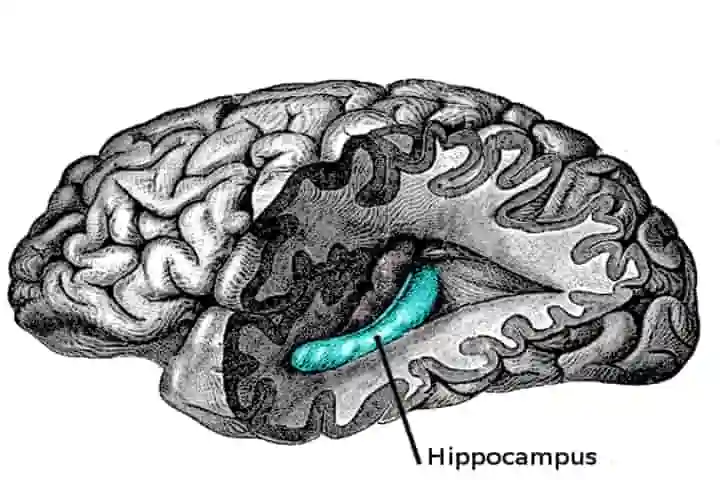

At the Center for Neuroscience at the University of California, Davis, a new study on brain imaging reflects that the brain's storyteller is the hippocampus as it connects and joins separate and even distant events to give them the shape of a single narrative.

This new study was published in Current Biology on September 29.

Briefing about the study, its first author, Brendan Cohn-Sheehy, who is a M.D./Ph.D. student at UC Davis said: "Things that happen in real life don't always connect directly, but we can remember the details of each event better if they form a coherent narrative.”

For the purpose of this study, Cohn-Sheehy and colleagues at Professor Charan Ranganath's Dynamic Memory Laboratory at the Center for Neuroscience used functional MRI for the purpose of imaging volunteers’ hippocampus as they learned and recollected a series of short stories.

For this study, stories were specifically created. Their attributes included main and side characters and also an incident. While some stories were made to have two part narratives that were connected, others did not.

In the fMRI scanner, the scientists played recordings of the stories to the volunteers. The following day, when the volunteers were asked to recollect the tales, they scanned them again. The main purpose of doing this exercise was to be able to contrast the activity and its patterns in the hippocampus, as the person learned the different stories, and later recalled them.

As per the expectations of the researchers there was a marked similarity for learning pieces of a coherent tale as compared to those that did not connect.

Also read: Why do humans not have tails – scientists solve the riddle

Cohn-Sheehy observed that results show the coherent memories being woven together. "When you get to the second event, you're reaching back to the first event and embedding part of it in the new memory," he said.

Following this, the scientists compared the hippocampal patterns which emerged during learning and retrieval. It was found that when stories with coherent narratives were recalled, the hippocampus activated more information about the second event than when recalling non-connected stories.

On this result, Cohn-Sheehy averred: "The second event is where the hippocampus is forming a connected memory.”

Testing the memory of the stories heard by the volunteers revealed to the researchers that the capacity to bring back hippocampal activity of the second event was related to the amount of detail the volunteers could recall.

Also read: Study suggests Roman Catholics of Goa and Mangalore were related to Gaud Saraswat Brahmins

Even though other brain parts are part of the process of memory, it seems that the hippocampus brings different pieces together across time and creates memories that are connected and narrative in nature, said Cohn-Sheehy.

This research represents the work of a new era in memory research. While traditionally neuroscience researchers studied the basic processes of memory in which disconnected information pieces were involved, psychology studied how memory functioned to capture and connect events in the “real world”. As per Cohn-Sheehy, these two are now starting to merge. He said: "We're using brain imaging to get at realistic memory processes.”

Studies and research in memory processes could help in better diagnosis and clinical tests of first and early stages of decline in memory either during aging or dementia. It could also assist in assessing memory damage from brain injuries.