At long last we have a millipede which justifies its name as it boasts of 1,300 legs! Derived from Latin, “millipede” means “thousand feet”, and till the discovery of this species, there was never one creature in its rank which had 1,000 legs!

The newly discovered millipede which has more legs than any other one on the Earth is found deep down the planet’s surface, according to a report in livescience.com.

Speaking about this new species, Paul Marek, the study’s lead author and an entomologist at Virginia Tech University remarked: "The word 'millipede' has always been a bit of a misnomer.” This is because the known millipedes have less number of legs than what their name implies. While several had less than 100 legs, the number one spot was held till now by the one living deep in the soil — Illacme plenipes – with 750 legs.

The newly discovered arthropod, Eumilipes Persephone, is now the one with maximum number of legs and one specimen that Marek examined has 1,306 legs.

Interestingly, the newly detected creature is named after Persephone, Zeus’ daughter, who was taken to the underworld by Hades.

Now for the physical attributes of the creature. Pale in appearance, it is eyeless and its body is long and threadlike while being 100 times longer than it is wide. The head is cone shaped and sports huge antennae which is necessary for it to navigate its dark world governed by odour while the beak is apt for feeding fungi. With so many legs to count, it makes the task difficult by coiling up like a watch spring, said Marek.

The legs of the creature also share vital information about its age.

Also read: Japan’s Snow Monkeys Survive Harsh Winter By ‘Fishing’ Live Creatures From Streams

Growing gradually and steadily, the millipedes, like the rings of the trees, add body segments during their lifetime. By counting these, entomologists come to know the age of different individuals of the same species.

Marek told Live Science: "I suspect these animals are extremely long-lived.” He examined four specimens, two females, two males with varied lengths and ages. The shortest with 198 rings had 778 legs while the longest with 1,306 legs counted 330 rings.

Basing the calculation on how frequently other millipede species add body segments, one can deduce that E. persephone typically lives to be between 5 and 10 years old in contrast to the two-year life span of other millipedes.

Significantly, this species will not be accessible for everyone as it was found 60 metres or 200 feet below the surface of the earth in an environment – banded iron formations and volcanic rock — which has been relatively unexplored.

This newly found species was first seen in Goldfields, located in Western Australia where extraction of minerals takes place. Marek informed that, wanting to search for cobalt and nickel, enterprises would drill narrow holes between 65 and 328 feet or 20 and 100 metres deep. In case there was nothing, these holes were capped and abandoned. "Some time ago, entomologists from Western Australia came up with the idea to sample these boreholes,” he informed.

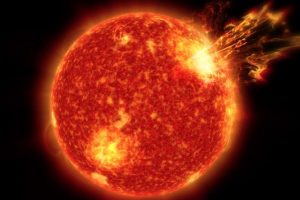

Also read: New study suggests Sun as the probable source of water on Earth

This was because these provided a window to see what was there in the subterranean ecosystems. They lowered leaf litter and other waste in cups to specified depths and waited patiently for weeks before taking them out. Researchers found varied life which thrived at these depths with the leggiest creature being one of them.

Study of the ecosystem at these depths is vital as the decomposers there recycle nutrients that surface life rely on while the creatures in deep soil layers filter toxins from our drinking water.

Still very little is known about them and their ecosystem. The new find will hopefully spur more research in this direction and as Marek pointed out that the find shows “there are a lot more discoveries to be made”.

"There's so much more biodiversity out there. We just don't have the full picture yet,” averred Marek.