Among the multiple regional and cultural expressions of the Mahabharata, the one from the Mewar School stands stands out for a galaxy of reasons.

Meticulously put together by Alok Bhalla and Chandra Prakash Deval, and published by Niyogi Books, ‘The Mahabharat: Mewari Miniature Paintings (1680-1698) By Allah Baksh’, unveiled here on September 14, is the fruition of eight years of persistent labour.

What makes this pictorial version of the (Mewari) Mahabharat unique is an entire set of distinct elements: The paintings, of course, but also the minute details captured in them; the age when this masterpiece was accomplished; and the artist Allah Baksh himself.

Allah Baksh’s miniature paintings inspired by the Mahabharata were commissioned by Maharaja Jai Singh of Udaipur, and were created between 1680 and 1698. From more than 4,000 such paintings depicting scenes from the Mahabharata, about 2,000 of them are published in this series of four volumes. A fifth volume of the series, with about 500 paintings depicting the Bhagavad Gita, was published previously.

Alok Bhalla, a well-known literary critic, explained that the Bhagavad Gita is distinctly depicted through vertical paintings by Allah Baksh; the Mahabharat series, on the other hand, is presented in horizontal paintings.

It is important to know why Allah Baksh and the age when this historical masterpiece was created, is important. “These paintings deserve an honoured place in the history of India’s miniature paintings,” Bhalla said. He drew an interesting distinction between worldviews of the poet (Ved Vyas) and the painter (Allah Baksh).

The poet tells stories of friendships, love and bravery that fade into irrelevance towards the end, because the epic ends on a note of lament for the passing of an age. The painter, on the other hand, is hopeful and his depiction of the Mahabharata takes the reader’s/viewer’s mind off sufferings. Allah Baksh maintains that since “no life is astrologically determined”, his outlook is full of hope. “Suffering is not a condition for life,” Bhalla said, underlining the painter’s philosophy.

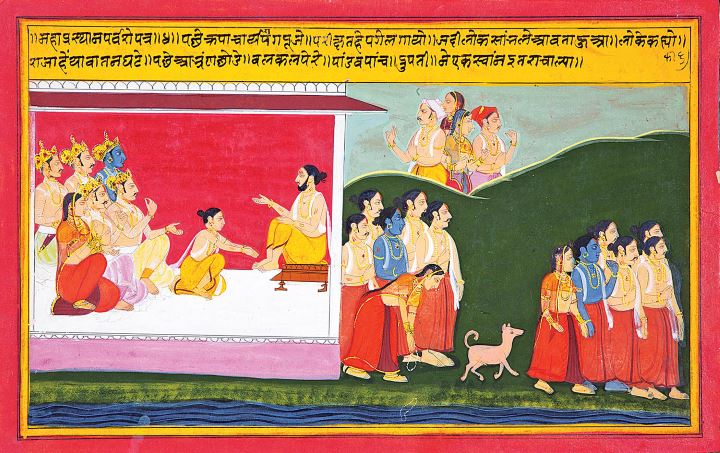

Talking about the distinctness of the depictions, Chandra Prakash Deval, a cultural historian and eminent Hindi and Rajasthani writer, shared some curious facts about the minute details depicted in the paintings. The paintings are so authentically reflective of the culture and reality of the Mewar region of Rajasthan, we can know people’s castes just by looking at their attire in the paintings.

Deval says there are more than 70 ways of tying the turban in Rajasthan, each depicting a different caste and region. Likewise, the attire of women in the paintings, with respect to the design of the outfit and the colours and prints embellishing it, one can tell the caste of the wearer. Besides, the paintings are an honest depiction of the flora, fauna, fruits and folk of Rajasthan’s Mewar region in that era.

Deval highlighted an interesting feature of this series: the very first painting that opens the first volume shows a dog among a pack of strays that enters the venue of a yajna. A person hits the dog, who goes and complains to his mother that he has been beaten up and illtreated for no fault of his — a dog does not know what a yajna is. The mother dog then came and cursed that man.

The moral of the story being non-violence and harmonious co-existence of all creatures. And the cover of the last volume carries the painting of a dog entering the gates of heaven in front of a group of humans (the Pandavas), signifying that no creature is superior to others.

The painting obviously has been inspired by the famous Mahabharata story about the journey of the Pandavas into their afterlife.

The distinguishing challenge of Allah Baksh’s work is that the selected portion of the Mahabharata to be depicted in his version was specifically text that was condensed to its briefest gist and then have its essence elaborated in a miniature painting, Deval pointed out.

This Mahabharata was translated from Sanskrit to Mewari to take it closer to both to Maharana Jai Singh and his subjects.

Speaking on the occasion, celebrated art historian Naman Ahuja brought to light yet another interesting feature of Allah Baksh’s rendition of the Mahabharata.

The Mewar School is significant as it “assiduously resisted the Mughal influence on art for the longest time, yet it manages to creep in” and it reflects in Allah Baksh’s work.

This was the time when there was a concerted effort to spread Mughal art across the empire and artists were directed accordingly. Allah Baksh, however, was adept in painting in both the Mughal and the traditional Mewari style.

As Bhalla put it, “The Mahabharata is not a nationalist chronicle, nor a view of Dharma as the dispassionate performance of one’s duty, nor a philosopher’s morality conundrum.”

He voiced his request to both the Rajasthan state and the Central governments to preserve this cultural heritage.

And with respect to Allah Baksh’s faith and its incompatibility with the core elements of Mahabharata — a deity, its physical depiction, worship, and the varying notions about heaven and afterlife, and so on — Bhalla quoted William Blake: “The worship of God is honouring His gifts in other men.”