Mao Ze Dong's famous dictum, "Power flows through the barrel of the gun”, may need to be tweaked in the digital age. Social media and OTT platforms have emerged as powerful tools to shape opinion to achieve political goals. The potency of digital firepower has only got enhanced as there is little regulation that can reign in messaging over cyberspace.

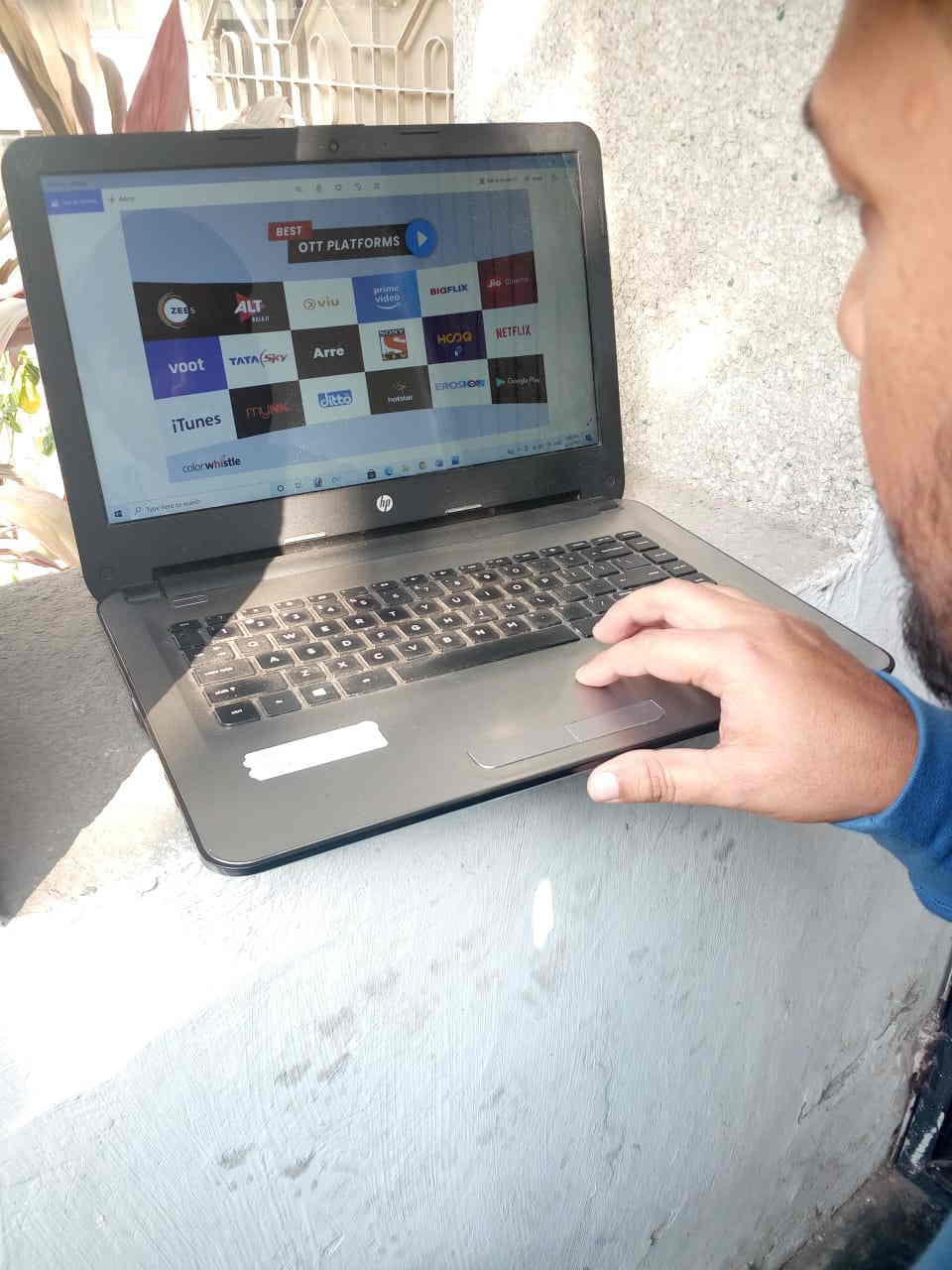

In India, OTT platforms have become a force to reckon with, where the majority of the population is below 30, and familiarity with digital tools is compounding at the speed of knots. With 40 OTTs in the country reaching around 40 million customers powering a market that is expected to cross $5 billion in 2023, there is a growing demand to regulate their content, thus making them answerable and suitable to Indian sensibilities and sensitivities, shaped by a unique 5000 year old civilizational history.

Potency of visual medium can’t be disputed. The imagery catches an individual’s imagination faster and gets imprinted on the psychic, thereby becoming permanent. Historically, visuals were effectively used by Hitler to propagate Nazism and spread anti-Semitism. At home, movies helped a south-based political party to popularise their ideology and capture power. During Cold War, Hollywood portrayed USSR and its allies as anti-West through their films and later, targeted West Asian countries and groups – all justifying US intervention in geopolitical affairs.

OTT regulation is not an off-the-cuff demand. Its corollary to instances when OTT content hurt public sentiments. While Amazon Prime’s Tandav series created a furore as some scenes in it made derogatory reference to Hindu gods, Mirzapur, web series courted controversy, when a petition in Supreme Court alleged that it maligned Uttar Pradesh’s image. Likewise, Netflix series, Leila showed the lynching of a Muslim and his wife being moved to a labour camp. Such images are bound to disturb public harmony and harm India’s social fabric.

Aware of the need to check such violations, the Union Government will soon come out with guidelines to monitor OTTs as confirmed by the Information and Broadcasting Minister, Prakash Javadekar in the Rajya Sabha. Last November the Government had brought all online platforms under the ambit of the I&B Ministry, making them register with the Ministry.

Not just India, but other countries too have laws to regulate oversee OTTs. Here is a bird’s eye view of the prevailing regulations in some countries.

Australia’s OTT segment is governed by its Broadcasting Service Act, 1992, laying down detailed guidelines on the type of online content hosted outside the country and those with Australian connection. Contents are classified as Refused Classification, which can’t be advertised, sold or imported in Australia; X18+ which is restricted to adults being sexually explicit in nature; R18+ for content restricted to adults as it is deemed high in impact and may be offensive to some sections of the adult community; and MA15+ restricted to viewers over the age of 15. Access to content of last three is restricted too.

Nearer home, in Singapore, the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), have issued a code of practices for OTT in 2018. Their content is classified as G for general; PG for parental guidance; PG13 for parental guidance for children below 13; NC16, not for children below 16 years; M18 for audiences 18 and above; and R21 restricted for those 21 years and above. Further services providers can offer NC16 content and above only if parental lock function is provided on the platform.

The R21 can be provided if is locked by default with the provider implementing a reliable age verification mechanism. Display of rating with elements in the content, which include nudity, theme, violence, sex, drug use, language and horror, is mandatory. The programmes should not erode the national or public interest and security or disturb religious or racial harmony.

The Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTUK) regulates and supervises radio, television and on-demand media services in Turkey. Its regulation mandates that joint stock companies be established locally with a licence for 10 years to provide such services. The license holders are to encrypt the audio and visual feeds, provide their access to the RTUK for remote monitoring while sharing various IP licenses with them to enable broadcast recording.

The Ministry of Communication and Informatics in Indonesia issued a regulation last November, requiring the OTT service providers, including foreign OTT service providers in the country, to register with the MOCI and moderate their contents. It is also said that the Indonesian Government will amend the existing law to add the OTT related provisions in the upcoming draft of the new Broadcasting Law. In 2016, Telkom had blocked Netflix which subsequently entered into a partnership with Telkom to unblock user access.

Even though Saudi Arabia does not seem to have any specific laws dealing with OTTs, it used its Anti-Cyber Crime Law to request Netflix remove an episode of Patriot Act. Deemed as critical of the Government, Netflix complied. The ACCL, is a short law with overarching powers.

Article 19 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the freedom of speech and expression, while Article 19 (2) allows Government to impose reasonable restrictions. The upcoming legal framework will need to finely balance creative freedom and the need to ensure that the nation’s unity and integrity is not endangered. The recourse could be a blend of unbiased self-regulation, legal framework and an option of an appellate body for appeal in case of unjustified curtailment.