The daily sordid tamasha in Pakistan is captured best by no other than Pakistanis themselves, both in media and movies, with a degree of courage almost unmatched in our part of the world. Defying deaths and threats, journalists and filmmakers perform surgery on shenanigans of military, mullahs, leaders and politicians with stoic nonchalance and professional excellence.

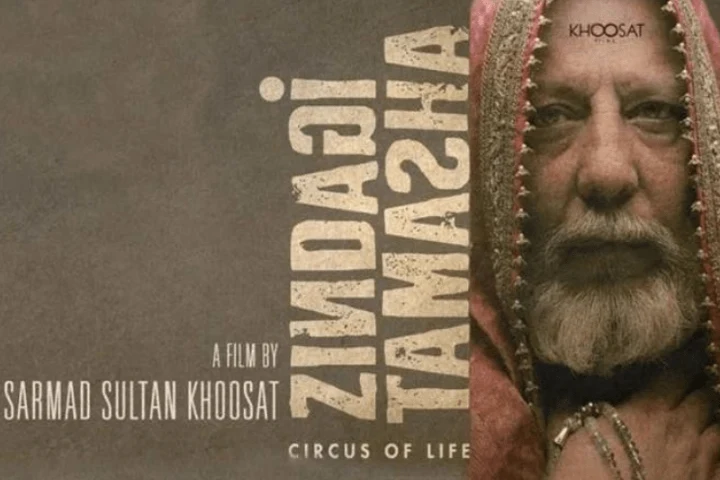

Of many, a signature name of such courage is Sarmad Sultan Khoosat. Grown up in a filmy family but conservative Pakistan, Khoosat walked into the forbidden alley with his 2019 home production Zindagi Tamasha.

A take on a man’s film-fuelled closet sexuality, his love for his Prophet, and society’s abhorrence for the former, negating the latter was to be released in 2019 when now ousted and jailed Imran Khan was selling dreams of Riyasat-e-Medina (State of Medina of Prophet’s time) and late Khadim Hussain Rizvi was running his own state within that riyasat in the name of protecting honour of the Prophet.

Even though cleared by three censor boards – Pakistan Central Censor Board, Sindh Censor Board and Punjab Censor Board – the movie had to face the test of Rizvi’s hardline Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) to reach theatres. The TLP team watched the movie and its cadres started brimming with anger, making Khoosat living with death threats thereafter.

This movie is the true depiction of the saying “When you show mirror to the society they become your enemies” . it shows the narrow mindedness of the people and society. When you held accountable for their deeds they will make you a worst example. #Sarmadkhosat #zindagitamasha pic.twitter.com/gZ1NaQIyL7

— Saad Khan (@Saadkhan15_) August 4, 2023

Khoosat wrote to PM Imran Khan to intervene but it didn’t work and his team left it to the TLP to take a call on the movie.

Zindagi Tamasha however proved to be a fascinating spectacle worldwide. It won accolades at Busan Film Festival 2019 and Asian Films Festival 2021. It surprisingly also became Pakistan’s official entry to the 93rd Oscar awards in 2021. It gave the world a taste of how beautifully two languages – Urdu and Punjabi – blend and weave verbal magic.

Four years after chasing former and new Pakistan rulers to prevail over mullahs to allow the film see the light of cinema halls; Khoosat finally premiered the movie on YouTube on August 4. Within three days, the movie has been watched by millions, majority of them Pakistanis.

So, what’s in the movie that made it a tinderbox of threats to guardians of morality in Pakistan?

Zindagi Tamasha (Circus of Life) takes its name from a classical Pakistani song that has haunted the protagonist of the movie like a soul from his childhood. Protagonist Rahat is a naat-khawan, a singer who sings in praise of Prophet Muhammad. His voice and piety have earned him esteem with which he proudly saunters through Lahore streets. He is lead naat-khawan of his mohalla and regales listeners on Eid-Milad-un-Nabi, Prophet’s birthday. His married daughter works for a TV channel and dreams to proudly call his father for a chat show one day. Rahat is also nursing his paralysed wife like a dutiful husband.

Besides naat, he sings sehra and rukhsati (poems for groom and bride) in weddings.

But the edifice of piety and fame of Rahat crumbled one night. On the occasion of a friend’s son’s wedding, he is coaxed by friends to dance. He does. But from his soul, to the tune of a song he has been infatuated with since childhood. He sways to the rhythm of Zindagi Tamasha Bani like a damsel, matching move by move. His femininity shocks even his friends, but they say nothing. A friend’s son captures his performance on the phone and uploads it on YouTube. The video goes viral.

Slowly, all those who know Rahat come to know of him dancing like a woman in a film song. People stop to say salam to him. His daughter chastises him, but convinces him to apologise in a video in presence of a maulvi to the whole nation of Pakistan. A maulvi is called and he apologises. But the maulvi is not convinced with his tauba (repentance), he wants it to stretch it into a dua (prayer) in favour of Palestinians and all Muslims world over. This irritates Rahat and a scuffle breaks out between him and maulvi. He refuses to apologise to the qaum (community) now.

But now life turns into a more miserable tamasha for him. His daughter loathes him now. Children are not even ready to accept niyaz (offering) from him. He is not even allowed to sing naat at the Eid-Milad-un-Nabi function. Instead, the maulvi there chases him away by singing a famous salam (lyrical poem) in praise of Prophet Muhammad written by Ahmed Raza Khan Barelwi.

Dejected, he returns to his paralysed wife, who senses that he has been boycotted and despite him telling her lies, she keeps her tears unto herself and shuts her eyes.

Assuming she has been put to sleep, Rahat returns to his room and starts watching his favourite movies. Few hours later, his daughter barges into the house to find that her mother has passed away. Now, Rahat’s life turns more pathetic, though some sympathies also come his way.

In the end, he watches and listens to the song Zindagi Tamasha Bani with abandon, but all alone in his misery.

This simple and gripping human story didn’t see the public screening in Pakistan because a religious “sufi” outfit which operates in the name of protecting Prophet’s honour and extols Prophet’s compassionate and forgiving attitude didn’t forgive a visual fictional story about a devout man who meandered only once and that too in a trance, without physically hurting anyone.

Rulers of Pakistan also didn’t show courage to stand up with an internationally-acclaimed movie that takes Pakistani cinematic art to a higher pedestal. Now, after being released online, the whole of Pakistan is watching it.

The closing lines of the flick perhaps capture state of both protagonist and Pakistan:

Zindagi Tamasha Bani,

Duniya Da Haasa Bani

(Life has become such a sad spectacle,

No more than amusement for the world)