Reflecting the despair of present times, reputed chronicler of world history, the New York Times, published an indicting report about India in 1973 – Decline of Urdu Feared in India. The backdrop of the report was post-1971 Bangla Liberation War scenario and heightened Hindu-Muslim tension in the northern parts of the country. However, 50 years after the NYT’s doomsday prophecy and similar concerns from some quarters now, the language is flourishing, producing poets, novelists, dramatists and scholars. Its ufaq (horizon) has actually widened to hitherto unknown ayyam (dimensions).

Most luminous aspect of the language is that Urdu continues to be the language whose poetry has been quoted the most in the Indian Parliament. A majority of songs in the Indian film industry, Hindi cinema or Bollywood, are composed and sung in this beautiful language and then they are hummed throughout India.

There are several universities that have been established exclusively to help Urdu flourish and maintain its academic and literary edge.

Largely the mother tongue of most Indian Muslims is Urdu, a language drawn freely from Persian, Arabic, Turkish and Sanskrit, it is also spoken by millions of Hindus and Sikhs in northern India.

Overall, Urdu is understood by about 45 per cent of the Indian population, mostly in northern states.

There are about 71.29 million native speakers of Urdu in India. As a percentage of the total population, the largest share of around 8 per cent is in Pakistan. A total of about 89.7 million people worldwide speak Urdu as their mother tongue, according to the website World Data.

Urdu is in fact being promoted in a myriad of mysterious and rigorous ways in India by individual Urdu lovers, professionals of arts, scholars, universities, academies, institutions, tailors, shopkeepers, chaiwallahs, libraries, and not to mention ever thriving mushairas (literary soirees).

NYT Report and Factual Rebuttal

The report directly declared that Urdu, an elegant language, has slipped into darkness in its homeland, India. The reason, the daily attributed to, was Hindu-Muslim divide along the language’s perceived association with religiosity, minority politics and Pakistan. Even then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, according to the NYT, saw the decline of the language owing to growing intolerance in the country.

Invocation of intolerance may remind us of similar “intolerance” that is believed to be prevailing in recent times. How come intolerance was prevailing during her Congress regime, perhaps only Indira could explain? Anyway, the language thrived, even in words of Indira and her colleagues, who quoted relevant Urdu couplets to drive their point home in the House of democracy and innumerable election rallies they addressed thence.

Interestingly, when many politicians from India were comfortably using Urdu poetry, including Prime Minister Mrs Gandhi, in their speeches and national broadcasts, then Pakistani President Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto struggled to speak in Urdu in public. The NYT reports this bizarre dilemma of Bhutto. But it also notes the root of the language problem: “When the subcontinent was divided in 1947, Pakistan made Urdu her official language and India chose Hindi… in the communal terror that followed partition, Urdu became an alien language in its birthplace.”

The report quotes legendary Urdu literary critic Professor Ale Ahmad Suroor who raised concern on the peril to Urdu. “Urdu is a national question. All democratic forces and secular-minded men should continue to plead the cause of Urdu,” he tells the NYT correspondent.

A year later, in 1974, Suroor was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for his seminal work Nazar aur Nazariya (Sight and Perspective).

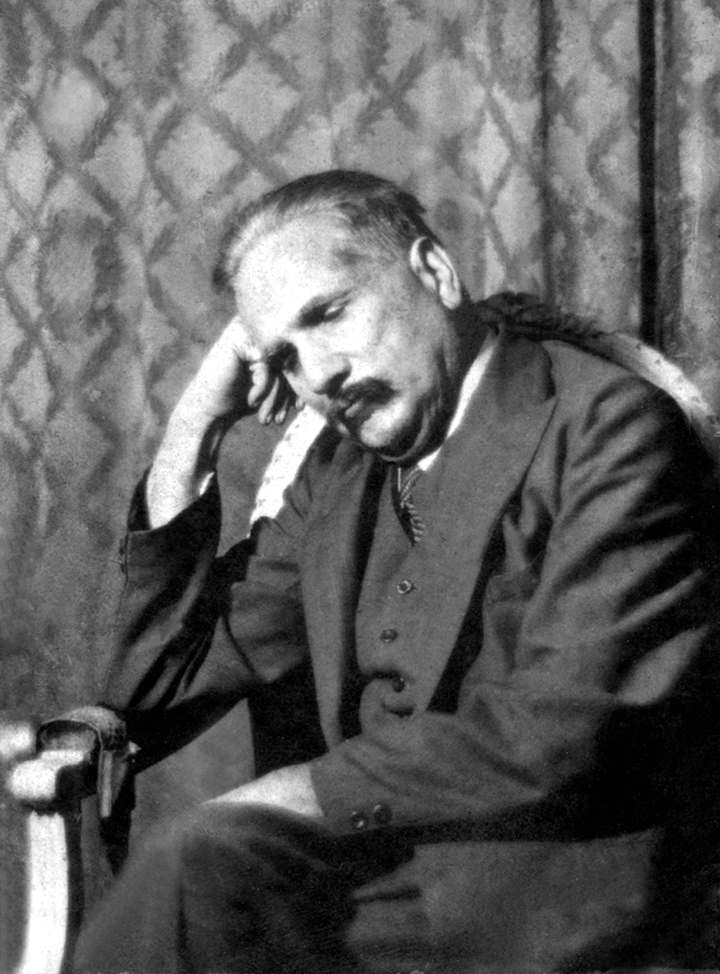

Suroor wrote extensively on Urdu poet Muhammad Iqbal, who is a national icon in Pakistan. Suroor was the founder director of the ‘Iqbal institute’ in Kashmir University which is now known as the ‘Iqbal Institute of Culture and Philosophy’. The ‘Iqbal Chair’ was established at Kashmir University in 1977 where Suroor was appointed as Iqbal professor.

Suroor’s success and accolades (he was later conferred Padmashri in 1991) proved that Urdu was promoted with as much passion after 1973 as it was feared to doom.

Iqbal, whom Pakistanis revere as a national poet (he was born and died an Indian), has been controversy’s favourite child. Some reference to his poetry or his role in pre-partition politics was removed in Delhi University’s undergraduate syllabus last month. Again, cynics were quick to predict doom for Urdu and its maestros in India. But Suroor’s work on Iqbal, a number of PhD thesis being continuously written on his craft and thoughts are testament that the bard’s philosophical-mystic poetry continue to enamour literature lovers and poetry connoisseurs in India.

In India, most of the Sahitya Akademi Awards given on Urdu criticism based on any poet’s work has been conferred on those who have explored various contours of Allama’s poetry and philosophy. The other poet similarly explored is Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib.

In addition, Iqbal remains the most quoted poet in Indian Parliament.

Few years back, the West Bengal Urdu Academy, which is one of the most active Urdu promoting bodies in the country, bestowed its highest award on Iqbal posthumously. Iqbal’s grandson Walid Iqbal flew to Kolkata to receive the award and famously said that Urdu is loved in India as much as in Pakistan.

Perhaps the same spirit was sprouted by KN Sud, former Hindustan Times editor and an Urdu lover in his response to the NYT reporter. “Urdu provides the most natural and powerful link among the countries in the subcontinent,” said Sud, “It has a role to play in its cultural emancipation. We must not let the current political controversies cloud the reality of our common past and future destiny.”

The realities of our times are not different and our spirit must be the same.

Rekhta, Largest Adda of Urdu

World’s largest collection of Urdu shayari, poetry & poets has one web address – Rekhta. Started as a website by the Rekhta Foundation in 2013, it has blossomed into a big project to preserve Urdu in every possible way – by creating the largest ever online database of books, running online libraries, organising annual fest (popular Jashn-e-Rekhta festival), social media campaigns, hosting literary evenings or mushairas, and even running a fortnightly magazine, Rekhta Rauzan.

The Rekhta Library Project, its books preservation initiative, has successfully digitised approximately 200,000 books over a span of ten years. These books primarily consist of Urdu, Hindi and Persian literature and encompass a wide range of genres, including biographies of poets, Urdu poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. They have been collected from libraries across the major cities of India such as Lucknow, Bhopal, Hyderabad, Aligarh, and Delhi.

Till June 2023, the site has digitalised more than 200,000 e-books with thirty-two million pages, which are categorically classified into different sections such as diaries, children’s literature, poetries, banned books, and translations, involving Urdu poetry. It is also credited for preserving 7,000 biographies of poets (worldwide), 70,000 ghazals, 28,000 couplets, 12,000 nazms, 6,836 literary videos, 2,127 audio files, 140,000 e-books manuscripts and pop magazines.

Rekhta has given platform to every Urdu poet of note, whether he has participated in any mushaira or not. Some madrasa graduates who excel in poetry and have been writing in nondescript magazines have found their work catalogued in Rekhta and it can be browsed anytime.

Urdu poetry, or more suitably Hindustani poetry, sometimes needs a linguistic guide to understand its meanings. The younger generations or people from non-Urdu & Hindi background need such an aide. For such readers, the Rekhta website has developed trilingual dictionary software. A reader can click on the difficult word and its meanings in three languages – Hindi, Urdu and English – will appear for him.

Even during the Covid lockdown, the Rekhta didn’t stop its activities and launched an “online mehfil” (live seasons) of literature, music and poetry across its social channels.

Its another initiative called Amozish organises e-learning to promote Urdu script.

Rekhta is owned by Sanjiv Saraf, an industrialist and an Urdu aficionado, who has learnt the language and made its promotion his passion. Though it is needless to say but since communal colour snatches some hues of Urdu, Saraf, Urdu’s most ardent servant, is a Hindu.

Tomes have been written about Rekhta serving Urdu. Some controversies have also erupted surrounding Rekhta’s promotion of Urdu. Few people say that Saraf is the salesman of the language of love and the sale of Urdu is adding to his business. Many purists scorned at Rekhta writing Urdu as Hindustani in one of its festivals. But, no one cite any other platform as humongously and rigorously serving Urdu, let alone plan of any individual or institution to preserve and promote the language, which is also called rekhta, as Rekhta is doing.

Jashn-e-Adab, Old Delhi

After Rekhta’s Sanjiv Saraf, the flag of Urdu hoists from another Hindu’s haveli – Ramswaroop Rai Ki Haveli in Koocha Ghasiram in Old Delhi. Literary activist Kunwar Ranjeet Chauhan of Jashn-e-Adab Society for Urdu Poetry and Literature has been organising Jashn-e-Adab here and other prominent places in the capital to celebrate Urdu and its poetry.

Like Rekhta’s festival, the Jashn too invites famous personalities from literature and performing arts to popularise Urdu, which according to Chauhan, is a language of people and they deserve to revel in its jashn. This fest also attracts Urdu enthusiasts from Pakistan and abroad who throng to see how the language is breathing in the heart of India and captivating its lovers like proverbial shama (flame) fascinates parwanas (moths).

Urdu on Stage

Another one-man force keeping flame of Urdu burning brighter is M. Sayeed Alam, an AMU alumnus. Sayeed is many characters rolled into one – he is playwright, actor, satirical poet, and if dramatists qualify as historians, he is one. He brought great Ghalib back to Delhi in Ghalib in New Delhi. A comic avatar of 19th century genius poet taking rebirth in 21st century Delhi is the most staged play of Alam. It never goes out of season in Delhi theatres.

Besides Ghalib, Alam has revived greats like Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Bahadur Shah Zafar on stage. All three played by late thespian Tom Alter. Alter, a devotee of Urdu, even wrote his autobiography in Urdu.

“Theatre protects a culture and its literature, and simultaneously makes it accessible to the masses,” Alam said in an interview. His theatre group is called Pierrot Troupe.

Big B, KL Sehgal are other notable plays of Alam.

Chaikhana, Waliullah Library and New Poetic Chums

As the evening sets, the streets in Old Delhi spring to life. Both – the labourers and literatti throng chaikhanas (tea houses). This is here the labourers find day’s newspapers and, despite the age of cellphone info addiction, wake up to the happenings in the world reading the printed headlines and in delirious discussions over intermittent sips of sugary tea. Such chaikhanas and their discussions run till dinner, and even later.

Among these chaikhanas, one is special. It is somewhat veiled from the gaze of bazaar crowd. Hidden in an alley of Chitli Qabar, it is a favourite meeting point of literary minds. Its old-style wooden chairs and tables remain occupied with minds that don’t discuss politics but poetry. “No city in the world has so many literary rendezvous as Delhi boasts. This one is one such station of weaver of words,” says Mohammed Anas Faizi, a famous RJ, satirical poet from Old Delhi while introducing this correspondent to aastana-e-sukhan (Threshold of letters).

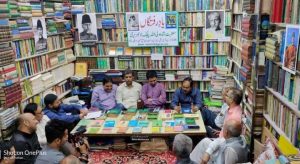

Few steps away from the Chaikhana towards the historic Jama Masjid is the historic Shah Waliullah Library, one of the oldest stations of literary souls in the capital. After literary enthusiasts, mostly fledgling poets and some veterans, are through their evening shots of tea and puffs of cigarettes, they come and sit on the mat of Waliullah Library to enliven the early night nashist (literary sitting). Here, the mehfil doesn’t stay limited to recitation of couplets and rendering of some delectable prose in a sonorous voice, participants often picks up books from the library (all prominent and relevant books of Urdu literature, including translations of Ramayana and Mahabhrata are shelfed in the library) and then weigh it on literary fulcrum.

A session at Waliullah library, says a participant, is almost like a university class on Urdu literature, if not more.

Faizi informs that poets of all ages and hues gather at these points. “Let me name a few: Nitin Kabir, Saavan Shukla, Rajiv Reyaz, Raaz Dehelvi and others,” says Faizi. Hindu poets, and that too young? He shrugs the unnecessary wonderment.

“We would be happy if Christians, Jews, Parsis, Buddhists, and others join us. We already have some agnostics among poets. The threshold of letters, like maikhana (tavern), welcomes all and it is worshipped by all. To allay your misgivings further that non-Muslims don’t know Urdu script and write in Devnagri, most of these Hindu poets know the script or they are learning it,” says Faizi.

He adds that the variety makes Indian poetry unique. “You won’t find so much variety of metaphors and figures of speech adorning poetry of other countries as they are found dwelling in verses of Indian poets. India is full of variety, and thus its poetry reflects that beauty,” says Faizi.

On beauty of Urdu and new-age poetry, Faizi recites his own couplet.

Woh Likh Kar Khoob Sharmaya Hamara Naam Urdu Mein

Mohabbat Kar Rahi Thee Chori Chori Kaam Urdu Mein

(My Beloved Blushed After Penning My Name in Urdu

And Thus Love Found Secret Route to Her Heart in Urdu)

Urdu in Parliament, Shops and Clothes

Aziz Ahmad Khan of Hapur has been a lover-preserver of Urdu. He was director of Al-Ameen Urdu Markaz, a body devoted to promotion and preservation of Urdu. He had compiled all documents related to debates over Urdu in Indian Parliament and with a missionary zeal he pursued the case of his favourite language with all the governments that came 1980’s onwards. Many ministers listened to his pleas and promised to increase grants of Urdu-promoting institutions and allocate funds for granting scholarships for students pursuing courses related to the language. His pleas among other efforts were the catalyst that paved the way for institution of Urdu universities in the country.

Besides, he kick-started a persuasive campaign to make common folks like shopkeepers, barbers and restaurant owners to make sure that they name their establishments in Urdu in addition to other languages. A number of people followed his advice and in cities like Hapur, Gajraula, Aligarh, Badayun and even Mumbai, people ensured that the board or hoarding at their premises has names inscribed in Urdu.

Taking inspiration from such initiative, a young Jamia Nagar-based fashion designer has started preparing clothes exclusively with Urdu carvings. He not only writes simple Urdu letters, but whole couplets of famous poets on dresses.

First Ever Translations

Social Science subjects like Political Science, Economics, History and Public Administration are taught in English medium at graduation level in almost all Urdu-medium colleges and universities, including those in Pakistan where the national and pedagogical language is Urdu. Recently, the Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad, is taking lead to translate such subjects. The Directorate of Distance Education of the varsity has rendered syllabi of some semester papers into Urdu. The task, according to Dr Naved Ashrafi, an assistant professor, has been arduous and interesting.

“Though simple, it was little known thus far that the Public Administration which was called awami intezamiya should perfectly be Nazm-o-Nask-e-Aamma. It was written and taught as public administration even in Urdu in many places. Similarly, while working more on the syllabus, we encountered a difficulty about how to translate classic terminologies like constitution, state, management, governance, administration etc. For instance, for state, Urdu words like riyasat, mamlekat, sooba etc are used. For constitution, we have aaeen and dastoor. Better use is defined by the context. After a lot of deliberation, we have come to this conclusion,” Ashrafi told the India Narrative.

He said that perhaps such translations, when complete, may be borrowed by Pakistani universities to be taught there.

Ashrafi’s words fortuitously finds echo in what Professor Khaliq Anjum of Delhi University told the New York Times correspondent.

“During the days of British rule in India, the alien government resorted to every device that could create a gulf between the Hindus and Muslims. The communal leadership of the Muslim League, tacitly supported by the Britishers, started building an impression that Urdu was the language of Muslims in India; the truth was completely different. Urdu was widely spoken and understood by all communities in a wide area.”

50 years later, Anjum, and Urdu, stand vindicated.