By Pushkar Sinha and Atul Aneja

India and China appear estranged if not hostile powers, as they try to script their rise in a world in flux. But scratch the surface, and India’s influence over Chinese psyche can be traced back at least to 65 A.D. In that year, Han emperor Ming-ti invited two Indian monks– Dharmaratna and Kasyapa Matanga– to China. These Buddhist holy men came with a number of sacred texts and relics. For the rest of their lives, they poured over these tomes and translated them into Chinese. In turn they established a powerful cultural connect between the people of India and China, which has not been extinguished to this day, despite contemporary setbacks.

Cultural osmosis between the two civilizations continued unabated, partly because of the exertions of a number of Central Asia missionaries. Names such as Lokottama, Sanghabhadra, Dharmaraksha, who translated Sanskrit texts into Chinese, continued to resonate long after they were gone.

The spread of Buddhism within China triggered an ardent desire among Chinese to visit the Buddhist holy land—India– setting in motion a dynamic that spanned centuries.

A by-product of this consummate spiritual and social exchange resulted in the birth of Serendian art—an offspring of Chinese and Indian art, inspired by the wisdom of Buddha.

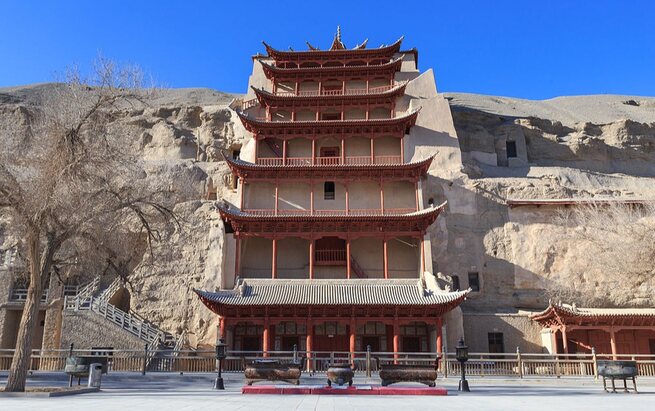

The grottoes at Dunhuang, in the bone-dry Gobi Desert—a drop on the ancient SilkRoad network– arguably preserve the best specimens of Serendian art.

There is a reason as to why Dunhuang became the epicenter of the India-China cultural fusion. A major point of intersection along the ancient Silk Road, Dunhuang was at the head of a branch line that descended into India.

The southern route of the Silk Road proved crucial in channeling a masterly artistic fusion that is vibrantly evident at Dunhuang’s magnificent Mogao caves.

The southern Silk Road passes through the other oasis settlements of Miran, Endere, Niya, Keriya and Khotan, before heading to Yarkand in China’s Xinjiang province.

From Yarkand, a major artery threaded through the lofty Karakoram Pass, leading to the exotic markets of Leh and Srinagar. The corridor finally descended through the plains before heading towards India’s western coast. It is segments of the southern silk road that are currently in deep contention between India and China.

While the merchants prospered, it was the monks, scholars and travelers passing through the Silk Road, who transmitted the essential message of Buddha to China.

Great Chinese scholars played a pivotal role in connecting the two ancient civilizations, eventually amplifying the spread of the Buddhist idiom in the region.

For instance, while at Tamralipiti, Fa-hien made drawings of Buddhist images and brought them to China. Hui-lun returned with a model of the Nalanda Mahavihara while Xuan Zang returned with several golden and sandalwood figures of the Buddha, apart from Buddhist texts which were subsequently translated. Wang Huan-ts’e, who went to India several times, collected many drawings of Buddhist images, including a copy of the Buddha image at Bodhgaya. This was deposited at the Imperial palace in China and served as a model of the image in Ko-ngai-see temple. Indians were also reported to have brought the most famous icon of East Asian Buddhism known as the “Udayana” image.

A Chinese writer tells us that there was no sculpture in three dimensions in China before the introduction of Buddhism. In his History of Chinese Sculpture, Omura suggests, “Images coming from India were considered holy” which significantly underlines the depth of Chinese acceptance of Indian thought.

By the end of the seventh century, Indian music began to achieve matchless popularity in northern China, when Buddhist monks brought the practice of chanting sacred texts during religious rites. Music reached China from India, via Kucha, Kashgar, Bokhara and Cambodia. Even Joseph Needham, the well-known advocate of Chinese cultural and scientific propriety admits, “Indian music came through Kucha to China just before the Sui period and had a great vogue there in the hands of exponents such as Ts’ao Miao-ta of Brahminical origin.”

By the end of the sixth century, Indian music had been given state recognition. During the T’ang period, Indian music was quite popular, especially the famous Rainbow Garment Dance melody.