In the midst of a gloomy international economic scenario, a piece of good news has popped up like a sunray on the horizon. Last month the global boycott of Uzbekistan cotton was lifted, a result of years of hard work by both the Uzbek government and the Uzbek people.

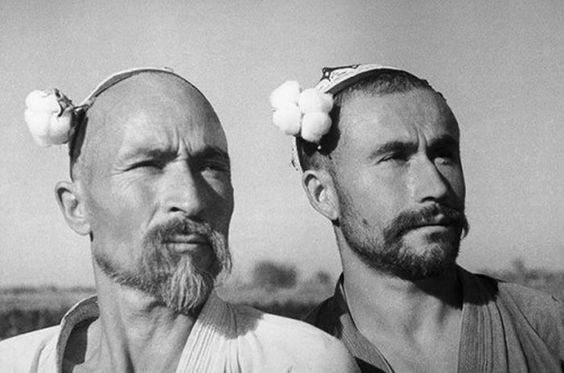

Cotton is the main cash crop of Uzbekistan and one of the mainstays of its economy. Cotton cultivation in the country dates back to a few centuries and it is the northernmost place where the crop is cultivated. At one time Uzbekistan ranked second among world cotton exporters. So important was the crop to the national economy that it was known as “white gold”. However, since its independence in 1991, the case was made that with its centralized and state system of cotton procurement the country was using forced labour, often child labour as entire families were used for harvesting this labour intensive crop.

Since 2011, 331 international brands and retailers had declared a boycott of cotton products from Uzbekistan over the use of child and forced labour during the harvest season of raw cotton. The Cotton Campaign was established to improve human rights in Uzbekistan and to permit the International Labour Organization (ILO) to monitor production in the country.

Now, however, all this is a thing of the past.

The international ban on Uzbek cotton has been lifted and a clarion call given to end the boycott of Uzbekistan's largest crop. An estimated two million children have been taken out of child labour and half a million adults out of forced labour since the reform process of the Uzbekistan’s cotton sector began seven years ago, says the ILO. According to its 2021 ILO Third-Party Monitoring Report of the Cotton Harvest in Uzbekistan based on eleven thousand interviews with cotton pickers, 99 per cent of those involved in the 2021 cotton harvest worked voluntarily. All provinces and districts had very few or no forced labour cases. A majority of cotton pickers who took part in interviews said that working conditions had improved since 2020.

Recently, in March 2022, a joint press briefing was held at the Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations of the Republic of Uzbekistan to discuss working conditions in the cotton sector of Uzbekistan. It noted that in five years, the country has walked through massive forced labour to its elimination. For the first time in its practice of conducting independent monitoring of forced labour since 2009, the Uzbek Human Rights Forum, a leading partner of the Cotton Campaign coalition, confirms the absence of systematic forced labour in the 2021 cotton harvest season.

Much of the credit for this accomplishment goes to President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who spearheaded path breaking reforms in Uzbekistan, including in labour policies. They began back in 2012 when Mirziyoyev was Prime Minister in the administration of then President Islam Karimov. According to the e Cotton Campaign in 2007, the Uzbek Government was forcing over 1 million children and adults, including medical staff, public sector employees and students, to pick cotton every year during the harvest. In early 2012, Mirziyoyev issued a decree banning children from working in the cotton fields. Now, as President, he has ushered in numerous reforms that include the modernization of the country’s former agricultural economic model and the eradication of child labour and forced labour in the annual cotton harvest that was previously prevalent.

Uzbekistan has taken historic steps in the fight against forced labour: the Government has criminalized the use of forced labour of adults and abolished quotas for cotton production, in accordance with the recommendations of the ILO and the World Bank the wages of pickers have been significantly raised and thereby the number of volunteers has dramatically increased.

Given the progress made in protecting the workers’ rights and completely eradicating systemic forced labour, the International Coalition Cotton Campaign announces an end to the call for a global boycott of Uzbek cotton.

Jonas Astrup, Chief Technical Advisor of the ILO TPM Project in Uzbekistan said that monitors observed new developments which indicate the democratization of the labour market in Uzbekistan. “For the first time, the minimum wage was consulted with not only the government but also the trade unions and employers of Uzbekistan. We also observed an emerging trend of collective bargaining at the grass-root level. Cotton pickers would engage in informal wage negotiations with farmers and textile clusters. Many pickers were paid well above the minimum wage as a result.”

Watch video

As the world’s sixth largest cotton producer, the lifting of the ban on Uzbek cotton is good news for the country and its economy. Many international exporters and brands like Marks and Spencer and H&M had kept away from Uzbek cotton.

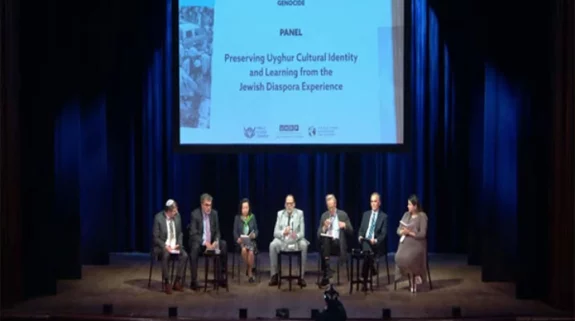

But there is now a strong possibility that these top brands, wary of sourcing cotton from Xinjiang in China, on account of suspected gross human rights violations will strongly return to Uzbekistan. “After an easing in a decade-long international boycott over forced labour, Uzbekistan, the world’s sixth-biggest cotton producer, is expecting to cash in as buyers turn their back on supplies from China,” says an article in the Hong Kong based South China Morning Post .

The daily points out that top brands boycotting Chinese cotton included H&M, on the advice of Better Cotton Initiative, an industry certification agent.

Sportswear brand Nike made a similar commitment, as did Ralph Lauren, Gap and American Eagle Outfitters, which explicitly prohibited their vendors and suppliers from sourcing any products or raw materials from Xinjiang, the newspaper said.

Watch video

Unsurprisingly, a major boost in exports is now expected and more cotton on the international market as well as more job creation in the domestic market. This is good for consumers worldwide as cotton prices have been escalating in the recent past to fill in the deficit between consumption and production – while global production of cotton for 2021-2022 was around 26.52 million bales, global consumption was nearly 27 million-plus bales. This will help stabilize prices.

The lifting of the ban on Uzbek cotton is also good news for India, which has seen rocketing prices, and is expecting a low yield this year. The government is mulling a ban on export; now it can now procure cotton at more affordable prices from Uzbekistan. This in turn will help deepen the already close bilateral economic cooperation between the two countries.

Also Read:

Why Central Asia needs to rediscover India

Will Pakistan’s instability shatter Uzbekistan’s connectivity dreams?

(Aditi Bhaduri is a columnist specialising in Eurasian geopolitics. Views expressed are personal and exclusive to India Narrative)