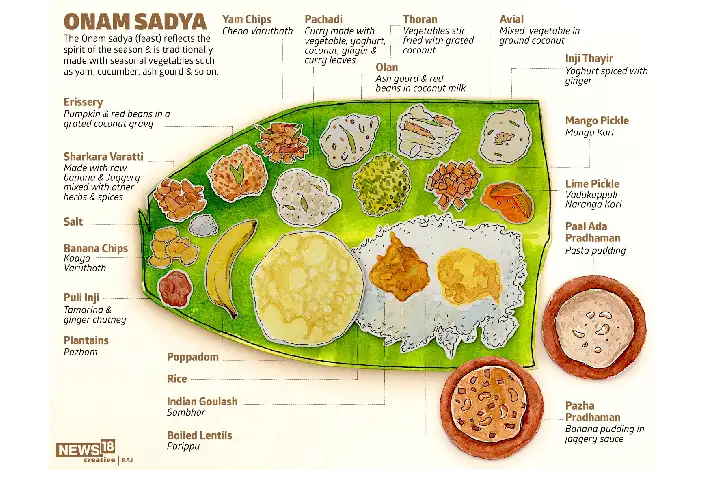

A few days ago, I had an Onam Sadya, a lavish vegetarian meal served on a banana leaf. The Sadya is a banquet cooked for special occasions like festivals and weddings. It is a ritualistic meal in the sense that the kind of dishes (salty, sweet, alkaline, sour, fried, gravies, dry, pickles, payasam, banana chips, as also a small ripe banana), their number (between 20-26) as well as the order in which these are served on the leaf, are all part of a well-established ritual.

In these days when Instagram generates “food trends”, the Sadya has become an annual Insta celebration, with restaurants vying to serve the maximum number of dishes, influencers posting reels eating red matta rice with their fingers, and most social media foodies dubbing this India’s “biggest thali”.

But this column is not about the Sadya, a delicious celebration no doubt. Instead, it is about the thali —a distinctive way of serving and eating food that came up in ancient India, and which is very different from the Russian service of formal western meals, where food is served in courses.

The banana leaf coastal southern and eastern India, is not just “auspicious” and thus apt for ritualistic meals like the Sadya, but is a disposable and eco-friendly plate or thali. In northern India, kansa or bronze thalis were traditionally used for meals eaten often within the kitchen itself by a family, and silver thalis were used by the elite. Community banquets however involved similar disposable thalis (and bowls) made from lotus or saal leaves stitched together in which multiple preparations would be served at the same time. We can still see this in rural, less urbanised areas, though this culture of eating on leaves is fading.

The metal thali or bowl has coexisted with leaf ones, and in fact, contrary to assumptions, the history goes back to ancient times. From Buddhist accounts, folklore, and iconography, we know of the existence of the metal bowl, carried by not just the Buddha but monks and bhikshus, who spread the philosophy and culture east and south of Magadh. These bhikshus would accept all food given to them in their bowl, thus eating a frugal though varied meal made up of various bits.

In fact, the origin of the thali even precedes the dispersal of Buddhist thought from India to the rest of Asia.

Rice was a strange crop to visitors from the western world to early India. These visitors from ancient Greece who followed in the wake of Alexander’s invasion in the 3rd century BC were more used to barley or wheat. Accounts from Alexander’s times thus remark on rice, its varieties and popularity in Indian diets, but and up also inadvertently giving us a picture of how this meal was served.

The Greek traveller, diplomat and explorer Megasthenese who was at Chandragupta Maurya’s court in Patliputra, for instance, wrote in Indica, the first account of India by a westerner (the book is lost but literary fragments found in other later works have been used to reconstruct portions) that, “When Indians are at supper, a table is placed before each person, this being like a tripod. There is placed on it a golden bowl, into which they first put rice, boiled as one would barley (chondros, made from barley was a staple of Greece), and then they add many dainties prepared according to Indian recipes” (World Literature and Thought, Donald S Gochberg).

From this account, the genesis of both the chowki and bowl/thali can be inferred. It is remarkable how till the late 19th and even early 20th centuries, many communities in India followed this exact style of service and eating–food served all together, placed on a thali or a round plate with raised edges similar to a bowl, which was kept on a chowki, whose ancestor, the three-legged table Megasthenese mentions too.

One of my favorite references on Indian cuisine is K. T. Achaya’s dictionary. There are others but this is one I refer to a lot. pic.twitter.com/F5vpltkVwx

— Nik Sharma (@abrowntable) July 26, 2019

Historian K T Achaya postulates that the “sthali” was a ritual cooking pot to boil rice in a traditional Vedic kitchen. “The name survives in a modified form in the thali of today”, he postulates in The Illustrated Foods of India. The metal plate with raised edges may have evolved from the pot of rice or the ancient bowl of Mauryan times, as the number of accompaniments to be eaten with the rice grew. Achaya also points out that the custom of metal thalis spread from northern India to other parts, though large banquets in which many people have to be fed, continued using cheaper, disposable leaves.

For those delving into the dispersal of ancient Indian cultures to the rest of Asia, it may be interesting to study dining rituals of most of south-east and east Asia, where rice is a blank canvas on to which many different types of preparations are placed and eaten —incorporating different tastes, vegetables and bits of protein, and condiments, along with a soup or a braised dish. These bowl meals are in fact much the same as the thali, or its early version—the Mauryan bowl.

what do you make of this bronze bowl with Griffins? from south Thailand nr major trading port Khao Sam Kaeo, thought to be from India, Mauryan to Sunga period (3rd BCE – 2nd CE) #griffin pic.twitter.com/Xym7l9WYTT

— Adrienne Mayor (@amayor) October 19, 2021

From the Japanese donburi (literally, bowl) consisting of fish/meat/vegetables simmered together and served over rice, to Korean bowl meals such as the bibimbap (rice, seasoned vegetables, meat, eggs, and a variety of toppings are combined), all have a resonance of not just the Buddhist bhikshu bowls, in which all sorts of flavours got in bhiksha (alms) combined, but of the way of eating described by Megasthenese.

This idea of eating rice or a main starch with a combination of diverse flavours in a single meal is symbolic too, not just “balanced” in the modern sense with carbs, proteins and vitamins. The idea of balance or harmony is central to Buddhist/ancient Indian thought, and we see this not just in the bowl meals of Asia, but as an underpinning to Indian cooking as a whole. The use of spices in India is in fact based on balancing doshas and gunas, as per Ayurveda, and balancing various flavours—sweet, sour, salty, astringent, bitter—even in a single dish. For instance, in a dish of bitter gourd in UP, the typical spice is fennel, with its sweet notes, and raw mango to incorporate the sour. Sometimes cooks use a dash of sugar to balance all these. This balancing of flavours in even within individual dishes is a hallmark of Thai cooking too, which has been influenced deeply.

If the Indian thali/bowl led to Asian gastronomy’s most distinctive feature, balance of flavours, western meals that follow the Russian service or service a la russe, are very different to this idea.

The Russian style of service adopted by most French restaurants and formal western dining became popular in the 19th century. Here, meals proceed in different courses, each served by a waiter. The idea is for every dish and a single ingredient in that dish to stand out instead of it being a melange of flavours, textures and colours.

Medieval French service was initially a jumble of dishes put together at the same time on a table, with lavish table arrangements and decorations to connote wealth and status. The Russian ambassador Alexander Kurakin is credited with bringing the new a la Russe service to France in 1810.

#FoodFacts: The French style was more grand, the Russian style had the advantage of your food being much hotter when reaching the diner, reducing the number of dishes & condiments on the table. The Russian Ambassador credited w/this was Alexander Kurakin | https://t.co/sVD0jEdIqz pic.twitter.com/0BHoJgshbi

— AbilenePublicLibrary (@AbileneLibrary) August 2, 2022

By the late 19th century, this new style had caught on not just in France but in England too. The new service reduced the number of dishes and food could be eaten hot, but it necessitated more staff such as footmen to serve the meal—as Downton Abbey fans no doubt know. Its influence can be seen in gastronomy even now, when high end restaurants follow this style.

But in Anglicised Bengali homes of the 19th century, this a la russe service was adopted to give the Bengali Thala a distinctive turn. A Bengali meal is served and eaten in courses too– bitters, vegetables, dal, fish, mutton, yoghurt, sweet and Paan follow each other in an organised progression but all are eaten with a central starch or rice like in every other Indian thali. This then is a merging of the eastern and western styles of eating: The thali broken up into courses.

Though, it isn’t as if the thali in all other parts of India, including of the Kokanastha brahmins in Maharashtra and in Karnataka, is not an ordered meal. What is placed first, and where on the leaf or metal thali is of ritualistic significance. Interestingly, salt, once the most important preservative and flavouring agent, a currency by itself in the ancient world (the word salary comes from salt), is placed first on every thali, along with lime, followed by chutney or pickles and fries, followed by a light, dry vegetable, and another with heavier spicing, which cannot precede the lighter vegetable and so on. Yoghurt, an important food in India, comes towards the end, along with milky sweets. Lighter and less spiced dishes are eaten before heavier ones, ending with yoghurt to soothe the stomach. This then is a broad structure to most Indian thalis.

Thalis in fact are ordered meals, contrary to what people believe, much like a western service. But they are balanced with small portions of different foods instead of the heavy protein centric courses of the West where one meat or ingredient dominates. It is this difference between balance and dominance, cultural, philosophic and culinary, that makes it so tough for most European or American chefs to understand the complexity of Indian flavours and spicing, and how notes can be layered and combined to produce a complex though harmonious whole.