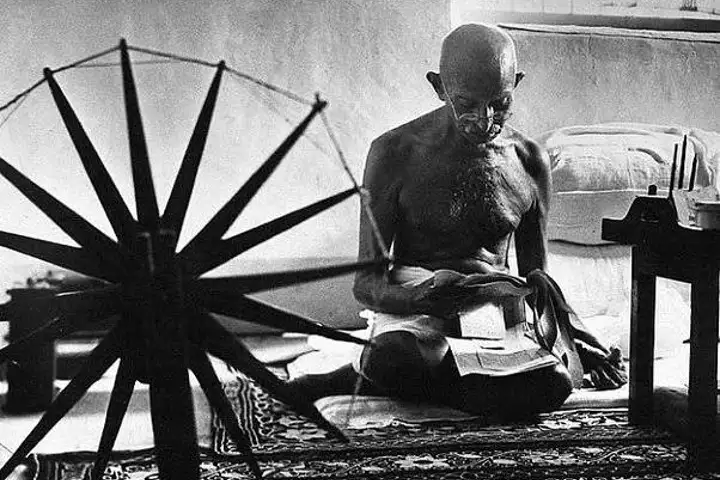

Pakistan marked its independence on August 14. A day later, India got its freedom. But for Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest soul among Indians and Pakistanis, these were ‘heart-break’ days. His heart was bleeding for the minorities in both the countries and hence, he wanted to spend August 15, 1947 in Pakistan, and moreover wished to settle there. This hitherto kept secret has been unveiled in renowned author MJ Akbar’s masterful study of Gandhi’s life in Gandhi’s Hinduism: The Struggle Against Islam (Bloomsbury Publication).

It was not tokenism, as many may believe, but Mahatma’s conviction. “He believed that faith could nurture the civilisational harmony of multi-faith India… he did not believe that faith could create artificial borders within a country… His concern was the immediate victims of partition: Hindus in Pakistan and Muslims in India,” the book describes.

The book informs that Gandhi wanted to be in Noakhali, East Pakistan, where Hindus had suffered bitterly in the 1946 riots and prevent any recurrence. Gandhi was still struggling to build hope from the incendiary debris of communal violence that Hindu-Muslim amity would return and prevail.

The book says that on May 31, 1947, Gandhi told Pathan leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan, known as 'Frontier Gandhi', that he wanted to visit the North West Frontier and live in Pakistan after independence. "

"… I don't believe in these divisions of the country. I am not going to ask anybody's permission. If they kill me for their defiance, I shall embrace death with a smiling face. That is, if Pakistan comes into existence, I intend to go there, tour it, live there and see what they do to me,” the book quotes him as saying.

This principled stand of Gandhi, says the book, didn’t emerge out of the blue but it remained consistent through the long and turbulent roller-coaster ride of high-voltage events.

"For more than 50 years, he sang, literally, from the same hymn sheet. Religion, said his hymn, was a catechism of love, tolerance and unity. Whether in South Africa or India, for over half of a century till the end of his public career in 1948, he explained why he was proud to be a Hindu," the book explains.

The writer traces the strong streak of religion in Gandhi’s life and politics to the upbringing he received at his home. He belonged to Pranami Sampradaya, founded in 17th century by Devchandra Maharaj (1582-1655), emerged during an era when the transformative policies of Mughal emperor Akbar were energizing the expanding Mughal domain with a new amity between predominantly Hindu population and a largely Muslim ruling elite. Pranami Dharma’s scripture, Kuljam Swaroop, was compiled after one of Devchandra’s disciples, Mahatma Prannathji (1618-94) travelled to Oman, Iran and Iraq. It incorporates pages from Bhagwad Gita, Vedas, Quran, Bible and Torah.

These Pranami values were served to Gandhi each morning with breakfast by his mother Putlibai, who taught him that all religions emerged from the same eternal being and that Vedas and Quran are both divine. Young Gandhi imbibed and kept these syncretic values as the most precious possession and they left an abiding, deep and lifelong influence on him.

When Gandhi became the leader of India’s freedom movement, his prayer meetings began with recitations from all major scriptures. He included the opening chapter of the Quran, the Surah Fatehah, in praise of the Rab Al Alamin,or Lord of the Universe, alongside the litany of multifaith prayers in his ashram.

Gandhi's personal and political life, writes Akbar, were fused by a humanism which believed that the unity of India, lay in acceptance of religious and cultural diversity, and its geography was a natural evolution of shared space between Hindus, Muslim Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis or indeed any community that had made this vast subcontinent its home.

He in fact, the book illustrates, claimed on many occasions: “I am a good Hindu and thus a good Muslim and good Christian as well.” On one instance he claimed before an audience that has Prophet Muhammad would come to earth now, he would find him a better Muslim than most of Muslims and that if Jesus would descend from Heaven, he would see in him an ideal Christian than in his own followers.

The book is full of such glimpses into Gandhi’s life where he emerges a true follower of all faiths. A number of Muslim League leaders, the book reveals, consider Gandhi a Mahatma, a great soul or darvesh.

It was his convictions in morality and ideal political behavior that he demanded the due share of Pakistan from the treasury be given to it, despite overwhelming opposition from some extremist groups in India. He however didn’t flinch and fell to the bullet for the sake of Pakistan.

Also read: Syed Mahmood’s legacy as colonial India’s dissenting judge

(Anas Mohammed is a Delhi-based journalist, specialising on issues related to Muslim Affairs. Views expressed are personal and exclusive to India Narrative)